-

chevron_right

Japan vs. Manga Piracy: $800m Losses & 100 New Pirate Sites in One Month

news.movim.eu / TorrentFreak · Thursday, 8 August, 2024 - 09:13 · 4 minutes

Last month, Japan-based anti-piracy group Authorized Books of Japan (ABJ) ran a newspaper advertising campaign in the United States, Italy, Spain, and France.

Its launch on July 17 was declared “Manga Day” and its purpose was to raise awareness of manga piracy by thanking those who pay for comics, rather than attacking those who do not pay. The ad below ran in the New York Times, with variants making an appearance in La Repubblica, El Pais, and Le Monde.

Most anti-piracy campaigns focus on negatives in the hope that fear overwhelms pirates to the extent they feel happier buying. ABJ’s campaign tries a different approach, one that has enjoyed success in Japan.

By showing appreciation towards people who pay ( “Thank you for reading official versions” ) it’s hoped that positivity will be better received and ultimately have a more lasting effect among manga’s continuously expanding fan base.

A Mountain to Climb

The world-famous news publications mentioned above have faced considerable challenges with the transition to digital, including unauthorized digital copies of their products being made available online by pirate sites. Yet, based on the sheer scale of piracy, none have experienced anything close to that taking place in the manga market.

When the campaign launched in the United States and Europe last month, ABJ reported that a total of 1,332 pirate sites, most dedicated to manga, were offering comics for free viewing online or otherwise making them available for download. The lion’s share is made available on a relatively small number of sites, mostly offering manga translated into English, and together pulling in billions of annual visits.

“The amount of free reading per month on the top 10 English translation piracy sites alone amounts to 800 million US dollars, a figure that is increasing every year and requires immediate action,” ABJ reported, citing figures from May 2024.

Recent Data on Manga Piracy

The reports supporting these claims aren’t usually made directly available in full. However, they do make appearances in support of presentations, seminars (videos of which sometimes appear on YouTube), and government meetings back in Japan. That often means that background documentation is available from public sources.

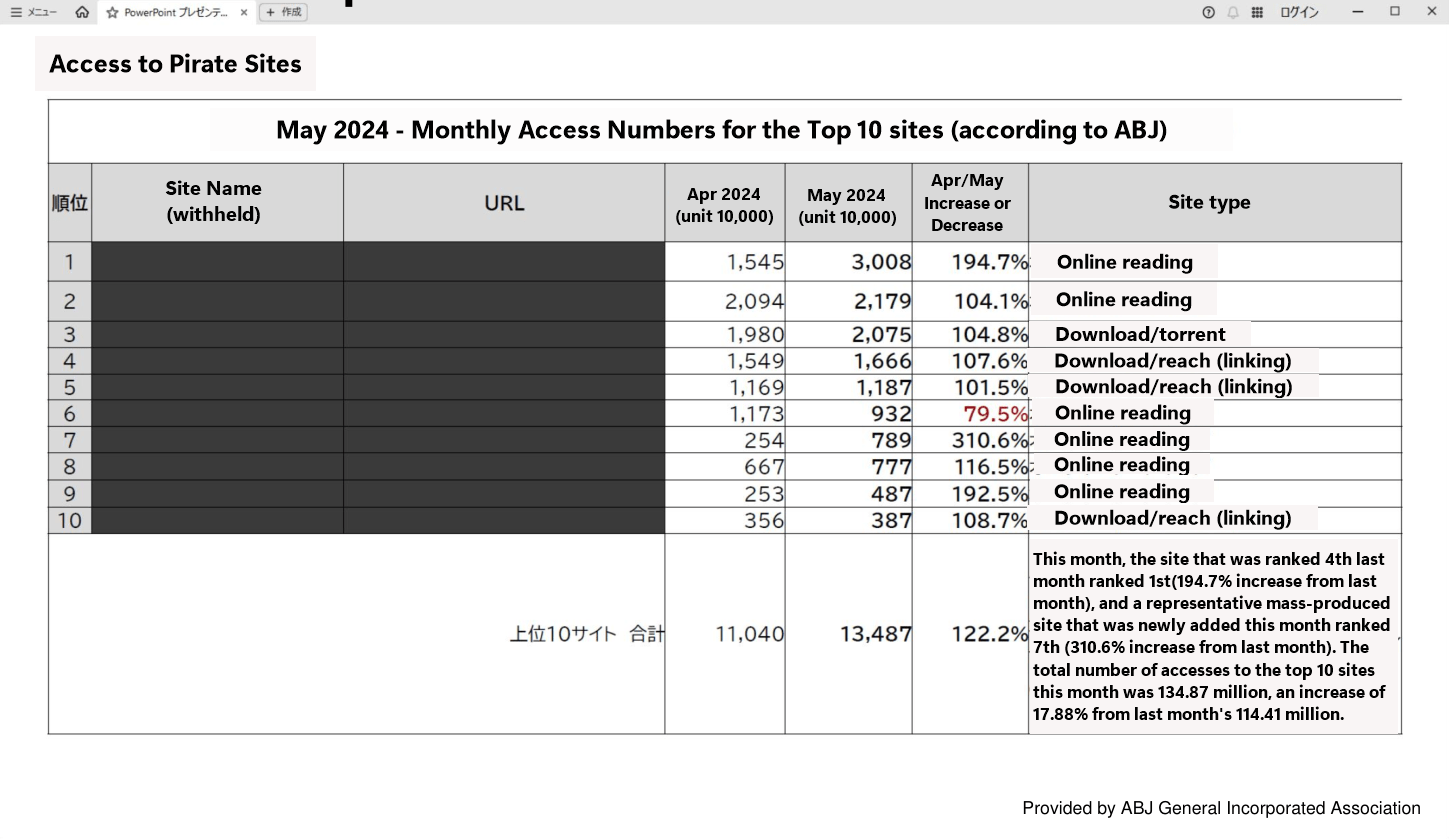

The first slide below relates to the Top 10 sites mentioned earlier; redactions are the work of ABJ, any English text represents our translations from Japanese to English.

One of the most striking aspects of this slide is the apparent massive growth of several sites in the top 10 over the space of just a month. ABJ reports that the site in the #1 position in May ranked #4 a month earlier in April after what appears to be a doubling of its traffic.

How the site managed to do that isn’t explained, but given the nature of the niche, where sites frequently disappear and rebrand, only to reappear, rinse and repeat, visitor numbers can fluctuate drastically before settling down again.

In a slide dated early July, ABJ states that “accesses have decreased due to the shutdown of large sites” but also cites concerns “over the emergence and growth of mass-produced sites by certain groups.” The anti-piracy organization doesn’t name the group, but it may be a reference to activity in Vietnam. Sites can give the impression of being mass-produced due to how quickly they disappear and reappear, while still managing to retain traffic despite new branding.

Another familiar scenario is outlined as follows: “Sites with the same content are provided via multiple domain names and CDNs. Images are stored in the same location or the same images are used.” Without specifics, it’s difficult to identify the sites in question, but this may be a reference to content sources remaining mostly static, with various front ends and domain names jumping around to give the impression of multiple moving targets.

It’s disorientating by design and can lead to the appearance of 100 new target sites in as little as a month.

Sites Cater to Various Audiences

As an indication of how site numbers can ebb and flow, ABJ reports that a total of 1,332 pirate sites were offering pirated manga in May 2024. Figures from February reveal a total of 1,207 sites, catering to various audiences. As broken down by ABJ, 294 sites were listed as catering to Japan, while 466 sites were offering English translations.

The remaining 477 sites were offering manga in languages other than Japanese or English, including Chinese, Vietnamese, Korean, Thai, Indonesian, Spanish, Portuguese, Russian, and Italian. By volume, English translation sites take the top slot overall, followed by Japanese language platforms and those offering content in Vietnamese.

Piracy Rates in Recent Years to Present Date

Research by ABJ estimates that free viewing of manga titles on pirate sites cost the industry the following amounts:

• 2020 – ~210 billion yen (estimated as of February 2021)

• 2021 – ~1.19 trillion yen (estimated as of February 2022)

• 2022 – ~506.9 billion yen (estimated as of February 2023)

• 2023 – ~381.8 billion yen (as of the end of January 2024)

The exact reason for the significant reduction in 2023 over the figures reported in 2022 is unknown, but ABJ identifies two possibilities. The first, “expedited measures” to remove links to pirated content from Google search results, which began during the fall of 2022. The second, “the unprecedented proliferation of the ongoing “STOP! Piracy Campaign.”

“We have built up various measures and realized a decrease of about 25% from 2022 to 2023,” ABJ explains.

The above is just the tip of a very large, coordinated effort, which also includes work by anti-piracy group CODA, to tackle piracy of all kinds of Japanese content, wherever it takes place. When the tide will conclusively turn is unknown, but the nature and scale of the effort suggests that it’s no longer the impossible mission it once appeared.

From: TF , for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

The Artificial Intelligence boom promises unparalleled progress but, in reality, it’s still early days.

The Artificial Intelligence boom promises unparalleled progress but, in reality, it’s still early days.

Last month, several major record labels

Last month, several major record labels

Every day, millions of people break the law; by posting copyrighted images, music, and videos on social media, for example.

Every day, millions of people break the law; by posting copyrighted images, music, and videos on social media, for example.

Faced with the growing popularity of ‘pirate’ libraries such as

Faced with the growing popularity of ‘pirate’ libraries such as